I’ve saved the best for last in my blog series on world building. Creating history for your world can really help bring some texture to an imagined world, giving it some foundation, and making it seem more real—just like the societies, cultures, and communities we find in our own world.

I’ve saved the best for last in my blog series on world building. Creating history for your world can really help bring some texture to an imagined world, giving it some foundation, and making it seem more real—just like the societies, cultures, and communities we find in our own world.

You can create history in a number of ways. In fact, it’s directly connected to two other key components of world building that I’ve discussed in earlier posts: culture and iconography.

But you can take it a step further, and have some fun in the process, by writing a myth, legend, folktale, newspaper article—essentially, an “exterior” story. To me, the great part about this type of writing means that you get to run around in your world without the pressure of heeding your novel’s main plot.

Some of this historical writing might purely be for you, the author. It will inform your portrayal of the world in your novel. But, then again, you may also want to include some of this writing in your novel, especially if it connects directly to your plot.

There are many ways to do this. Some authors write myths for their world and include them at the beginning of their novels. David Eddings did this in his Belgariad series, as his myth established the central plot problem in his world.

There are many ways to do this. Some authors write myths for their world and include them at the beginning of their novels. David Eddings did this in his Belgariad series, as his myth established the central plot problem in his world.

Many of my creative writing stories like this format, in which they start their books with long-winded myths. I generally find myself turning off. Personally, I prefer it when authors weave their myths into the tapestry of their narrative. I’m just not sure how much readers will care about a myth (unless it’s really engaging, like the Belgariad myth) until they understand how it relates or impacts the protagonist. So I prefer that the myths inform my characters (and their journeys) along the way.

We can look at some of the other fantasy masters for inspiration.

In Harry Potter, J.K. Rowling has written many exterior stories. Some of these she used in a whole other book, The Tales of Beedle the Bard. One of the tales contained in the book, “The Tale of the Three Brothers,” is core to the plot in the original Harry Potter books.

In Harry Potter, J.K. Rowling has written many exterior stories. Some of these she used in a whole other book, The Tales of Beedle the Bard. One of the tales contained in the book, “The Tale of the Three Brothers,” is core to the plot in the original Harry Potter books.

C.S. Lewis did a similar thing with Narnia. Even though The Magician’s Nephew is chronologically the first book in The Chronicles of Narnia, it is actually the book that Lewis wrote sixth. It’s essentially a prequel.

“This is a very important story,” wrote C.S. Lewis about The Magician’s Nephew, “because it shows how all the comings and goings between our own world and the Land of Narnia first began.” As a child, I adored this book, because it explained how the wardrobe and the lamppost came to be—not to mention all of Narnia.

J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth is abundant in exterior stories, mostly myths and legends. It’s one of the reasons his world is so compelling. He often incorporates his myths right into the narrative, having characters relate them to each other, as is the case with the myth of the one ring.

I have to say my favourite example of including myths in a novel can be found in Watership Down by Richard Adams.

Throughout the book, the rabbit characters tell stories of the trickster folk hero, El-ahrairah. The tales serve to inspire the rabbits and give them courage during their journeys—or simply to entertain them, depending on what is happening in that particular scene. By the end of the book, the reader comes to realize that the culture of the rabbits absorbs all heroic characters and remembers them in the form of El-ahrairah; he is a composite of many heroic figures, including Hazel, the hero of Watership Down. It was these myths that made me fall in love with this book as a child.

I’ve tried to follow the lead of some of these great authors in my own writing, preferring to include my myths as part of the overall story. For example, in Kendra Kandlestar and the Door to Unger, we get to read along with Kendra the “The Tale of the Wizard Greeve.”

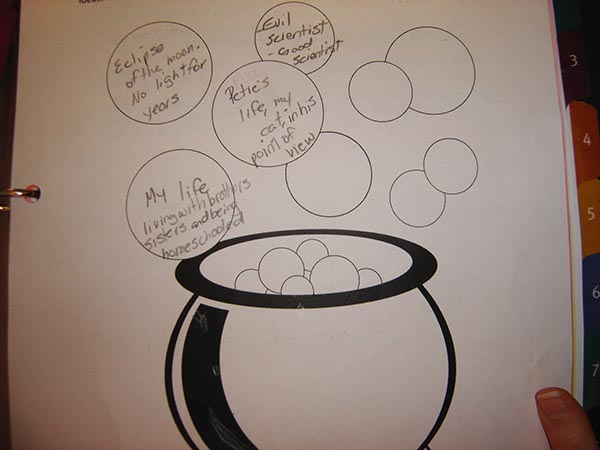

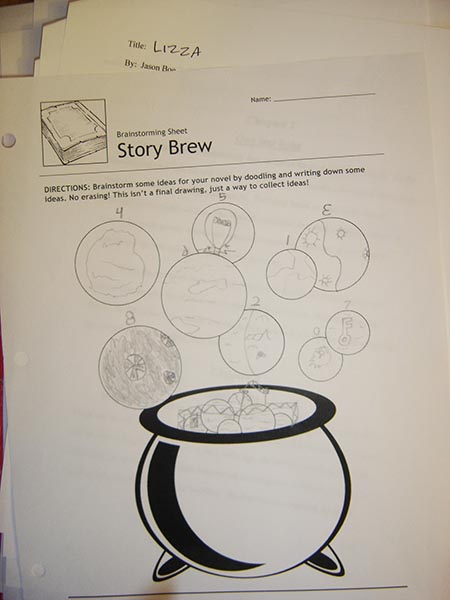

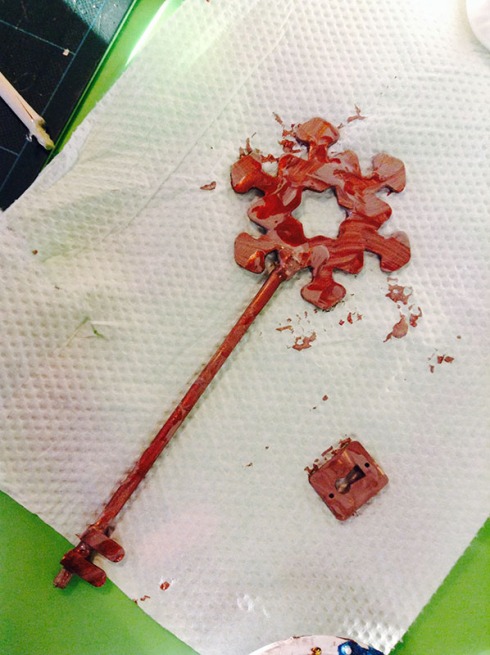

Here’s a photo of my sketchbook, where this myth first took shape.

In fact, many short stories and tales that are connected to Kendra Kandlestar’s Land of Een begin in my sketchbook. I’ve written dozens of them. Many of them are about how a town in the Land of Een was given a particular name or about how a particular aspect of the Land of Een came to be. The majority of these tales don’t appear in the Kendra Kandlestar books themselves, but I have included many of them on my website, as part of an online “Eencyclopedia.”

I’ve been talking mostly about fantasy writing here, but it’s important to emphasize that you can employ this technique of building history for all sorts of genres. After all, the purpose here is to make the world that your characters walk around in seem real. So if a myth doesn’t fit your particular genre, you could try other devices such as newspaper articles, TV reports, or letters written by long-deceased relatives of the characters.

One of my young creative writing students recently chose to do a newspaper article to connect with his novel. He really was inspired:

* * *

Well, that’s my series on world building. Ultimately, I think it just comes down to making up a set of logic, and then making sure you live by that logic. It can take some time to do this, of course, but I think it’s worth it. It will ultimately make the overall writing process flow more smoothly. And, in the meantime, it’s a whole lot of fun!